On the Eastern Shore of Virginia, the historic Brownsville Plantation home now stands as the gateway to the longest expanse of coastal wilderness remaining on the East Coast

Story by Ian Post | Photo by Gordon Campbell / At Altitude

Brownsville-by-the-Sea

Just east of Nassawadox, in Northampton County, VA, a 200-year-old home known as Brownsville stands on the Brownsville Preserve, the headquarters for The Nature Conservancy’s Virginia Volgenau Coastal Reserve. Woven into this environmentally protected property are histories that exemplify how people have interacted with the land on the Eastern Shore of Virginia — multigenerational agricultural operations, crops attracting birds hunted by presidents and enslaving Black people for labor.

Written records related to Brownsville date back to the 1652 and 1655 patents to John Browne for 1,262 acres “near the river of Mathepungo [Machipongo].” After Browne’s daughter, Sarah, later inherited the tract with her husband, Arthur Upshur, the farm was passed down and held by the Upshur family for over 300 years, until TNC purchased it in 1978. As on most multigenerational family farms on the Eastern Shore, nearly all of the Brownsville Upshurs were buried in the family cemetery on the property.

In 1691, the Old Hall was the first residence built on the property and was 20 feet wide by 35 feet long, complete with four rooms, a small hall, an attic and, according to Historic Virginia Homes and Churches, “some curious little closets in the upstairs rooms.” The Old Hall became the home of the people enslaved at Brownsville in 1806 and later, in 1898, was moved across Upshur Creek as a tenant home until it fell into ruins in the 1960s.

Just west of the Old Hall, at the cost of $10,000 in 1806, John Upshur led the construction of the home that stands at Brownsville today. According to the National Historic Registry report, “Brownsville is a two-story brick structure with a gable roof and one interior end chimney…[with] walls…finely laid in Flemish bond with white marble lintels over the windows.”

In 1809, John Upshur added a one-and-a-half-story frame wing to accommodate visiting relatives, declaring, “There is no place to put the sole of my foot.” One of the chief distinctions of the home, however, is its interior Federal woodworking, especially the “drawing room trim with the applied decoration on the mantel and the tassel-and-swag decoration on the chair rail.” Similar decorative woodworking and notably detailed craftsmanship can be found in the interiors of other historic Eastern Shore homes, like Ker Place, Wharton Place, and Eyre Hall, but the craftsman responsible for this work has yet to be identified.

Today, historic Brownsville is part of The Nature Conservancy’s Volgenau Virginia Coast Reserve (VVCR), and the home is opened to the public twice annually for a Holiday Open House and a spring Open Farm Day. The Brownsville Preserve also offers visitors unique natural experiences through its trails and educational and community outreach programs. The VVCR protects 14 undeveloped barrier and marsh islands in addition to the Brownsville Preserve, which provides a critical wildlife habitat and safeguards the Eastern Shore from storm surges and sea-level rise.

At the helm of TNC VVCR is the director, Jill Bieri. She says, “With our partners, we have protected 133,000 acres — barrier islands, marshes, upland forests, agricultural land, shrub-scrub habitat — making it both a year-round home and a stop over for hundreds of species of birds.” From the boardwalk and trails traversing the historic farm, visitors can see deer, fox, raccoons, blue herons, bald eagles, wild turkeys, and many other species of birds. Bieri adds, “Brownsville Preserve is a wonderful place to work with access to the walking trails, the old farm roads, both Phillips and Upshur Creek, migratory and resident-bird habitat and the opportunity to share this special place where we work with the community, our partners and global colleagues is very special.”

A Tale of Two Abels

For nearly two and a half centuries, Black people were enslaved for agricultural, industrial and domestic labor on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. Brownsville and the broader Upshur family were not exceptions, and, in fact, several Upshurs defended the institution in both politics and during the Civil War. Although much has been written about the slaveholders, researchers must dive deep into archival records to discover even basic information, like names and birthdates, about enslaved people.

In 1850 and 1860, censuses of enslaved people across the United States were recorded, listing only the slaveholders’ names, with the age and gender of each enslaved person. The 1860 slave schedule for Brownsville lists 35 people enslaved by William B. Upshur, ranging in age from 1 to 78 and living in seven dwellings on the property. By cross-referencing several other records, it’s possible to learn the potential name of one of the 14-year-old boys enslaved at Brownsville.

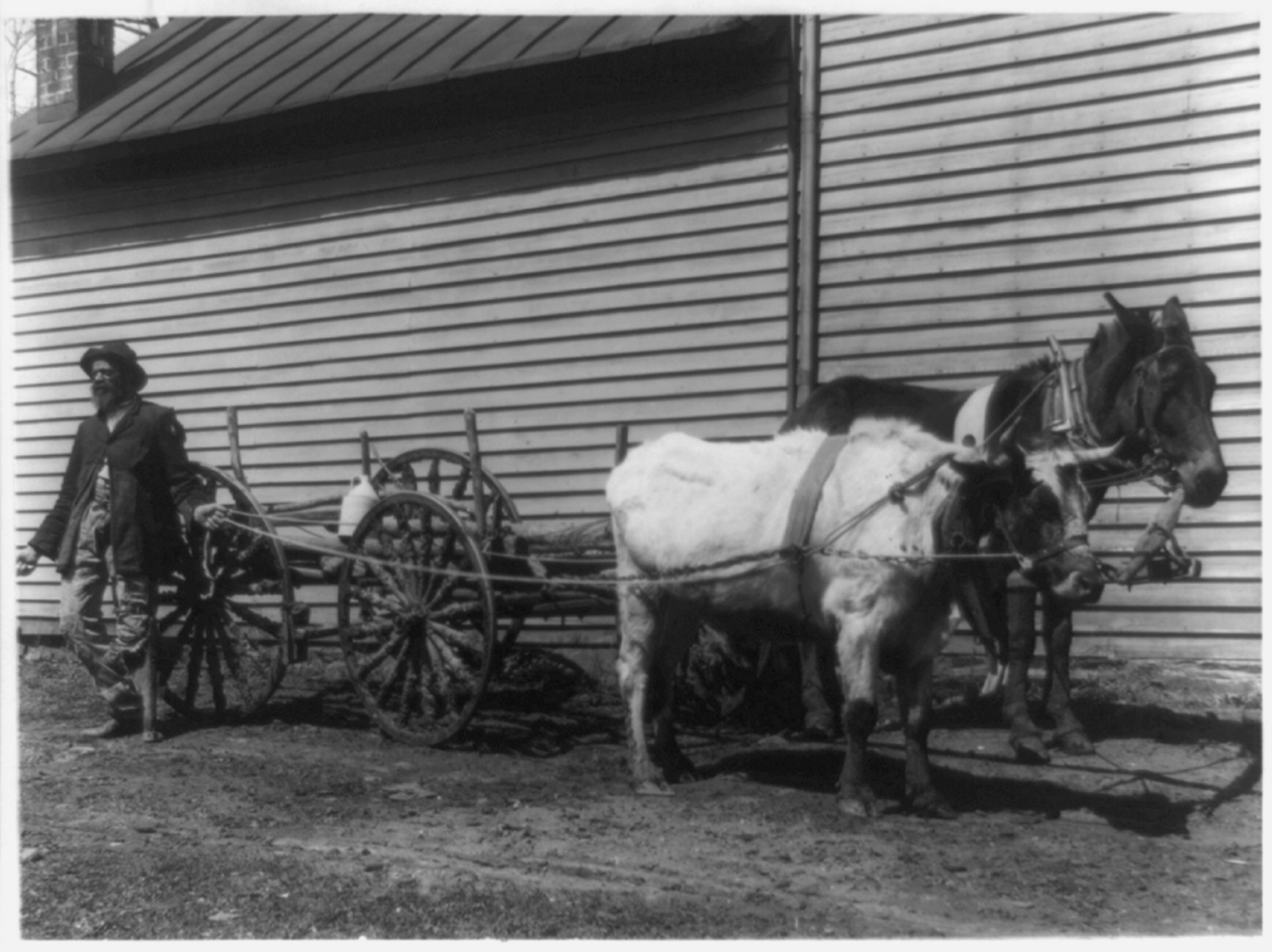

A 1912 obituary published in the Peninsula Enterprise for Abel Upshur of Accomack notes that he was formerly enslaved by William B. Upshur of Brownsville. Using birth information from his death certificate and census records, it’s possible that Abel was the 14-year-old male listed on the 1860 slave schedule. Moreover, the death certificate lists a rarity for formerly enslaved people — the names of his parents, Parker Leatherbury and Leah Upshur. After gaining his freedom, Uncle Abe, as he was reportedly known, became a drayman (brewery worker) in Accomack and later a sexton of the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church. Unfortunately, information about his enslavement — and the enslavement of others — at Brownsville is scarce to this date.

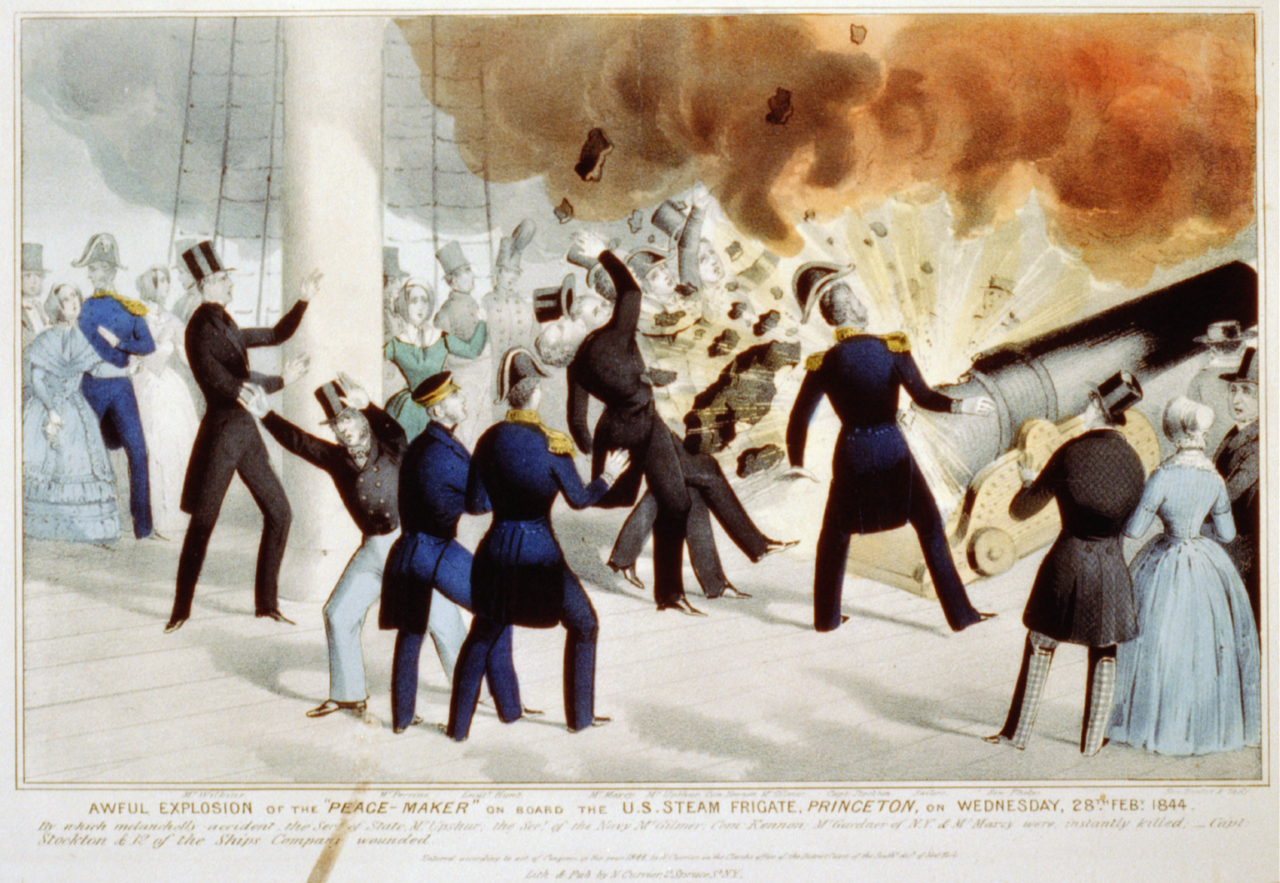

On the other hand, on the bayside of Virginia’s Eastern Shore, an incredible amount of information exists on an infamous figure in the family — Abel Parker Upshur. Cousins of the Upshurs of Brownsville, Abel P. Upshur’s political career began when he led a student rebellion at Princeton in 1807 and ended fatally aboard the USS Princeton in 1844. At his Eastern Shore home, called Vaucluse — which stands today — he entertained national figures, including President John Tyler, for whom Upshur served as secretary of the Navy from 1841 to 1843, when he was named secretary of state. In these positions, and earlier in his career as an attorney, judge and state legislator, Upshur was a vocal defender of slaveholding and states’ rights.

At the State Department, Upshur wouldn’t live to see his diplomatic legacy — the annexation of the Republic of Texas. According to a letter he sent to the U.S. envoy to Texas, Upshur believed that it was Great Britain’s “general plan” to “abolish domestic slavery throughout the entire continent and islands of America.” However, on February 28, 1844, a first-of-its-kind screw-propeller sloop, called the USS Princeton, steamed up the Potomac River on a ceremonial trip that would end up killing six and injuring 16 to 20 people. After several times demonstrating the ship’s heaviest gun, ironically named The Peacemaker, it accidentally exploded and sent iron shrapnel into the crowd. Upshur was killed along with Secretary of the Navy Thomas Walker Gilmer, Captain Beverley Kennon, Maryland attorney Virgil Maxcy, New York lawyer and politician David Gardiner, and President Tyler’s enslaved valet, Armistead. Upshur’s treaty for the annexation of Texas was secured by President Tyler in 1844, and Texas became a slaveholding state later,

in 1845.

In contrast with Abel Parker Upshur, learning more about the enslaved Abel Upshur — who was possibly named after the former — requires challenging historical research. But by diving into archival collections and reassessing records kept by slaveholding families, new generations of researchers and descendants can shed light on people of the past who were voiceless and nameless throughout their lifetimes.

The Birds and the Beans

As a multigenerational family farm, Brownsville has seen many different crops grown on the land, beginning with tobacco in the early Colonial period and continuously cycling staple crops, like barley and corn. Records also show that the Upshurs at times produced other products, like salt, rose water and, interestingly, castor oil.

Although castor bean production in the United States is primarily found in southwestern states today, there were five castor oil mills (including Brownsville) on the Eastern Shore of Virginia in 1835. At Brownsville, where 800 acres of castor beans once grew, the castor oil was shipped to places like New York for use in paint, medicine and beauty products.

In 1892, Brownsville’s castor bean-loving quail attracted a noteworthy visitor: President-Elect Grover Cleveland. After becoming the first and only president elected for a second term non-consecutively, defeating Benjamin Harrison in a rematch of the closely contested 1888 election, Cleveland sought a nearby hunting vacation. With his schooner docked at Cobb Island, President-Elect Cleveland hunted duck and snipe with members of the hunting club at Broadwater on the sparsely populated Hog Island. Despite delays from the blustery November weather, Cleveland also traveled inland to hunt quail at Brownsville with Thomas T. Upshur, a historian and former colonel in the Confederate Army.

Photo by Gordon Campbell / At Altitude

Today, the Brownsville Preserve attracts dozens of species of migratory and non-migratory birds. Tidewater and marsh habitats protected by TNC provide ample feeding ground for these aviary visitors. According to TNC VVCR director Jill Bieri, “This time of year, we see thousands of nesting shorebirds and waterbirds (piping plover, American oystercatcher, terns, skimmers) on the barrier islands and in the coastal lagoon system on the seaside — we also annually monitor those populations and have for nearly 50 years. Spring also brings long-distance migrants (i.e., whimbrel) who depend on the intact habitats as a fueling stopover as they head north to their nesting grounds.”

In partnership with the Virginia Department of Wildlife Resources’ Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program, the Brownsville Preserve also manages shallow-water impoundments and hedgerows that enhance habitat for birds as part of the Wildlife Enhancement Program. The undeveloped and uninhabited conditions of the Brownsville Preserve and its surrounding barrier islands make the conditions perfect for environmental and biological research conducted at the VVCR.

1 comment

I’m interested in the history and present day status of Cobb Island for a historical feature on the damages inflicted on Virginia over the years by hurricanes.

I would be grateful for any relevant information and thank you

C Brian Kelly

Beststor3ies@gmail.com

P.s. I used to know your president Tom Richards years ago when covering the Arlington County Board.