WATCHFUL EYE Chris Judy, shellfish director for Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources in Annapolis, patrols the grounds of the state’s oyster sanctuary on the Severn River.

Maryland’s Department Of Natural Resources

Says Its Sanctuary Program Is Benefiting Watermen

Chris Judy shared a couple of intriguing ideas that could help commercial watermen across the Eastern Shore with oyster harvests.

But it was more than Judy, Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources Shellfish Director, talking out loud about allowing controlled harvests in waterways protected under the state’s sanctuary program. “Two scenarios have actually been put on the table,” Judy said, referring to DNR officials discussing possibly rolling back sanctuary boundaries, so watermen can harvest areas adjacent to the protected waterways, or allowing watermen to use devices that would remove spat, oyster larvae attached to shells or other surfaces, to harvest in other bodies of water.

“If we could work together more effectively,” Judy said, “I think the sanctuary could remain protected and still provide benefits to the fishery. I think there’s a win-win if we could work better together. If people could talk through the issues and work together, a limited, managed harvest in the sanctuary could provide harvest and replenish itself to provide ecological benefits.”

That may be easier said than done, Judy said, “because we need people to work together instead of scream across a table.”

The state’s sanctuary program, which has kept 51 waterways off limits to commercial harvesting since 2010, remains a work in progress regarding the impact on an up-and-down oyster industry that reportedly has struggled in the past year.

HELPING HAND Chris Judy checks on the status of oysters at Maryland’s Department of Natural Resources Severn River Sanctuary located outside of Annapolis.

“The program is committed to restoring oysters in 10 tributary scale sanctuaries by 2025,”

Judy said.

Five sanctuaries headlining the program — Harris Creek, Little Choptank River, Manokin River, Tred Avon River and Upper St. Mary’s River in Maryland — haven’t produced enough data to spark optimism among commercial watermen, primarily because Harris Creek remains the only completed sanctuary. However, Judy said, these sanctuaries show promise of becoming self-sustaining sanctuaries.

Five sanctuaries headlining the program — Harris Creek, Little Choptank River, Manokin River, Tred Avon River and Upper St. Mary’s River in Maryland — haven’t produced enough data to spark optimism among commercial watermen, primarily because Harris Creek remains the only completed sanctuary. However, Judy said, these sanctuaries show promise of becoming self-sustaining sanctuaries.

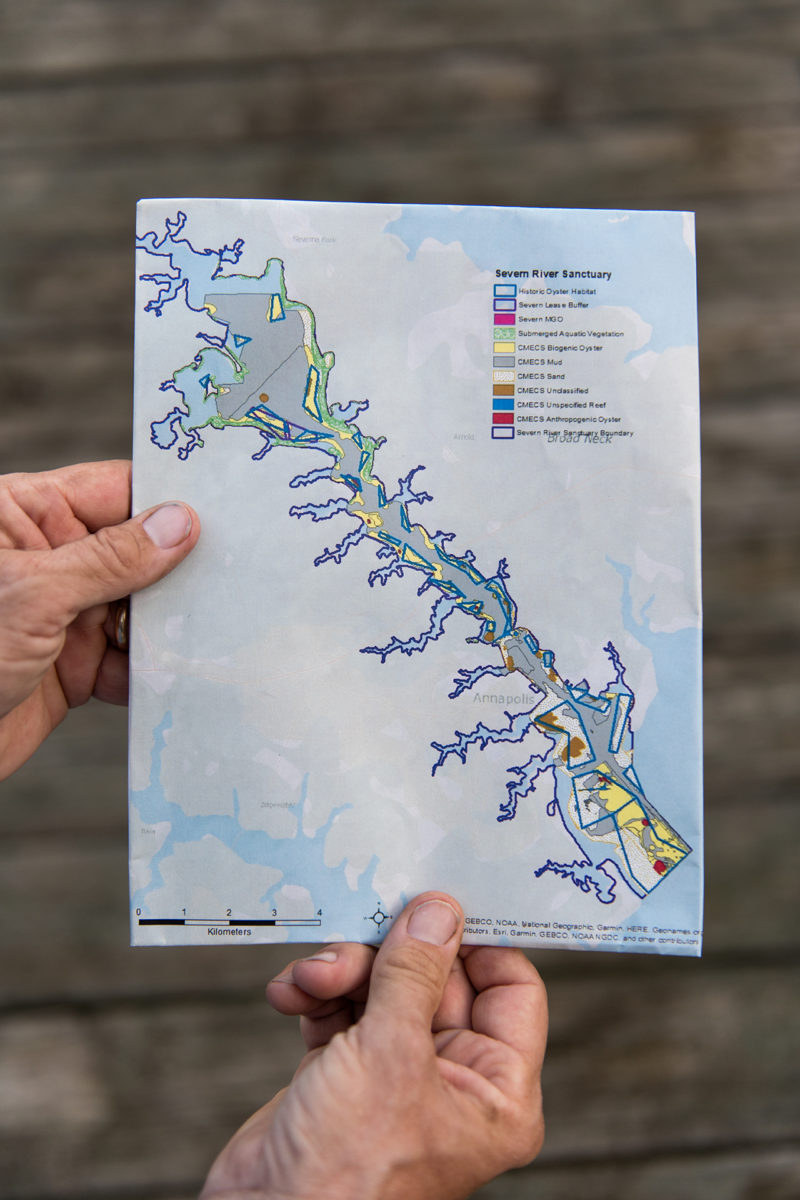

GROUND COVER The Severn River Sanctuary and Restoration Project extends from Annapolis northwestward about 10 miles. This water is well-suited to support disease-free oyster growth.

Most initially have met the state’s minimum standard of 15 oysters per square meter and ultimate goal of 50 or more oysters per square meter. Still, one question remains unanswered: “Do these sanctuaries provide oysters to areas outside their boundaries?” Judy said. The hope, he added, is for sanctuaries to “produce oyster larvae that move with currents” that “will repopulate harvest areas that are adjacent to the sanctuaries.” Commercial watermen likely will have to wait longer than they would like.

State officials, like Talbot County Watermen’s Association president and longtime commercial watermen Jeff Harrison said, “We would have spill-over. That’s not happening. In fact, we’re going in the opposite direction. We were doing better without sanctuaries.”

Judy understands why commercial watermen like Harrison feel that way. Sanctuaries have had a “negative impact on the fishery initially. Sanctuary programs are not designed to have immediate benefit to fisheries,” Judy said. “Some of the areas that were closed have a long history of being valuable to the fishery.”

Still, he envisions a day when commercial watermen will benefit from sanctuaries. “I could see it happen. I hope it happens. Everyone hopes it happens,” Judy said. “But will it happen? We’ll just have to wait and see.”

Story by Victor Fernandes

Photos by Jay Fleming